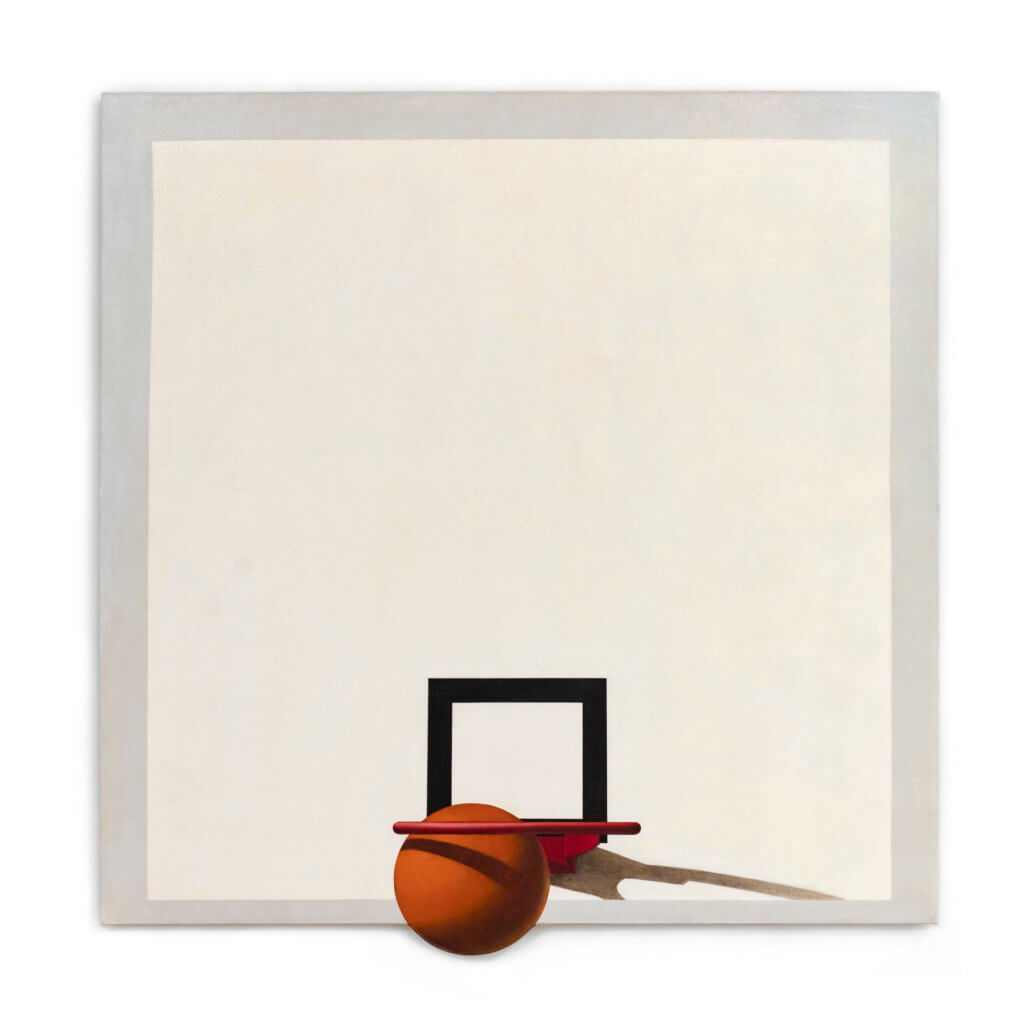

MOE BROOKER: He made these images that were stark. You had a basketball and a backboard confronting you and saying, “This is who I am, this is my strength, you can’t take this away from me, I can control this.” There’s no way in the world that you could mistake it, at least for me, the intent. The portraits absolutely put it right in your face: “I am who I am. We are who we are. You have to confront my image, you have to confront me.” The relationship between the two was brilliant—that he was able to take those images, and get across the message about who he was as a painter: “Here I am, you deal with it.”

JACK SHAINMAN, GALLERIST: I always thought [the Basketball Paintings] were really interesting. I remember asking Barkley about them, too, and he talked about this kind of beauty and poetry of basketball. He told me that they’re like portraits, and I never really knew what he meant until I saw the triptych [Father, Son, and…] They’re almost like religious paintings. They certainly harken back to that.

RICHARD POWELL, PhD, ART HISTORIAN, DUKE UNIVERSITY:: These are Philadelphia paintings. They come out of his engagement with the art world and also the black community. It can be easy to zoom in on these basketball paintings and zoom in on his play with geometry, but there’s more to it than that. There are real people, real lives there despite the fact that we don’t see them in the painting. He’s saying, what about a black reality that has to do with those who are not viewed as carriers of great high culture? This is not just elevating the culture to a spiritual level, it’s the beauty of moving across the space to put the ball in the hoop. Behind these pristine city abstractions of space and form is the poetry and the choreography and the floating of Wilt the Stilt. These things are art unto themselves. And it took Barkley Hendricks to concretize that. One also doesn’t want to lose sight that simultaneously to these paintings, he is doing portraits. And he’s doing portraits of these same young men.

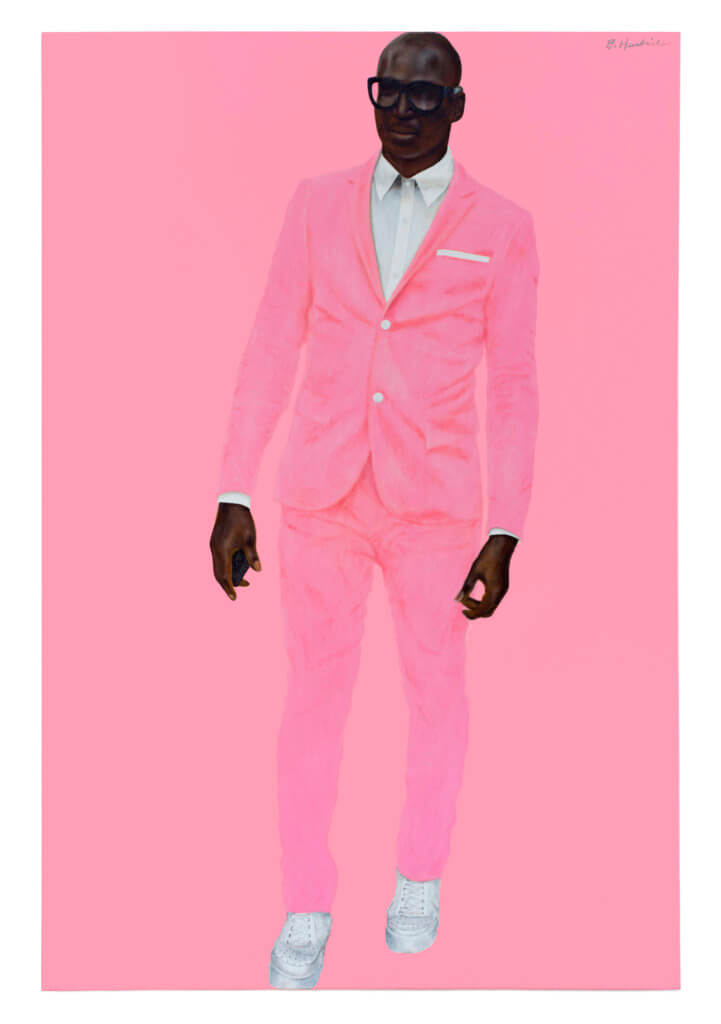

ELLIOT PERRY, NBA POINT GUARD 1991 – 2002, CONTEMPORARY ART COLLECTOR: Obviously I played basketball, but what resonates with me and what resonated the first time I ever saw a Barkley Hendricks painting was, “That’s me.” Or, “That’s my family member.” There is a direct and instant connection and gravitation to that work. They just sort of bring back memories—not just the style, but the way he painted with pure clarity.

HANK WILLIS THOMAS: He had a painting of a person named Jules, who was a family friend, and there was either a postcard or print of that in my aunt’s house. Speechless is the only way to really describe it. I don’t think I’d ever seen a painting of a person of African descent that was like that. It said as much about style and grace as it did about beauty and technical ability. I never thought that I’d make a work of art that was as timeless and affective as those. It definitely is kind of like... that’s the goal.

TREVOR SCHOONMAKER, CURATOR, BIRTH OF THE COOL RETROSPECTIVE: They feel like disparate bodies of work just because people know the portraits, and because people haven’t seen the Basketball Paintings. They were made simultaneously. The basketball paintings give a lot of insight into how he came up to his idea of monochromatic flat planes of color behind his figures. The basketball paintings are planes of color and geometric fields. They are feeding into one another.

NICK CAVE, ARTIST: I saw a number of these [basketball] paintings and I was literally shocked that they came from Barkley. I would have never guessed that he was working in this direction. They’re just so modern. And so graphic. I see Barkley as a figurative painter. But then I started to think about it, and I got really caught up in this whole notion of time. I think that came about when I started to pay attention to the shadows on the rims. The subtleness of how that rim is lit on that edge. You know it’s like 9:30 at night. The physical presence of the body is very much part of this work although it’s not present. You can still feel the action. You feel how time is part of a collective experience and you would find yourself with your friends and community for the entire day. You really feel like you’re on the court.